On this page

History of BMEC

The need for a new hospital was evident before the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1939, a site had been agreed near the Queen Elizabeth Hospital and funds in excess of £3 million was put aside. The 1939-45 war prevented progress. Post-war new plans were made the site was again confirmed in 1946 and the hope expressed that ‘State Control’ in 1948 would not hinder the development, but it did!

Several plans were agreed and abandoned. Several had reached detailed planning stages with completion dates announced, before being abruptly cancelled to start again from scratch. There were several attempts to close the hospital and replace it with the staff scattered in small district hospitals. These would not include a research or academic facilities.

There were several attempts to close the Birmingham & Midland Eye Hospital completely and open small departments in all the district hospitals. This would seriously affect the work that the hospital had been doing in advancing ophthalmology. Fortunately the staff of the BMEH had been united in proposing that the service in Birmingham be provided by a major unit with three smaller peripheral units, but the staffing would be integrated.

Finally, after 112 years at Church Street (1884 – 1996), the hospital moved to its present location on Dudley Road, and was once more renamed as the Birmingham and Midland Eye Centre. The new centre included an accident and emergency department, outpatient suites, four operating theatres, ophthalmic imaging, visual function department, optometry department, orthoptic department, day surgery unit, an ophthalmic in-patient ward and an Academic Unit of the University of Birmingham. The Birmingham and Midland Eye Centre was officially opened by HRH Prince Andrew on Friday, 28th June 1996.

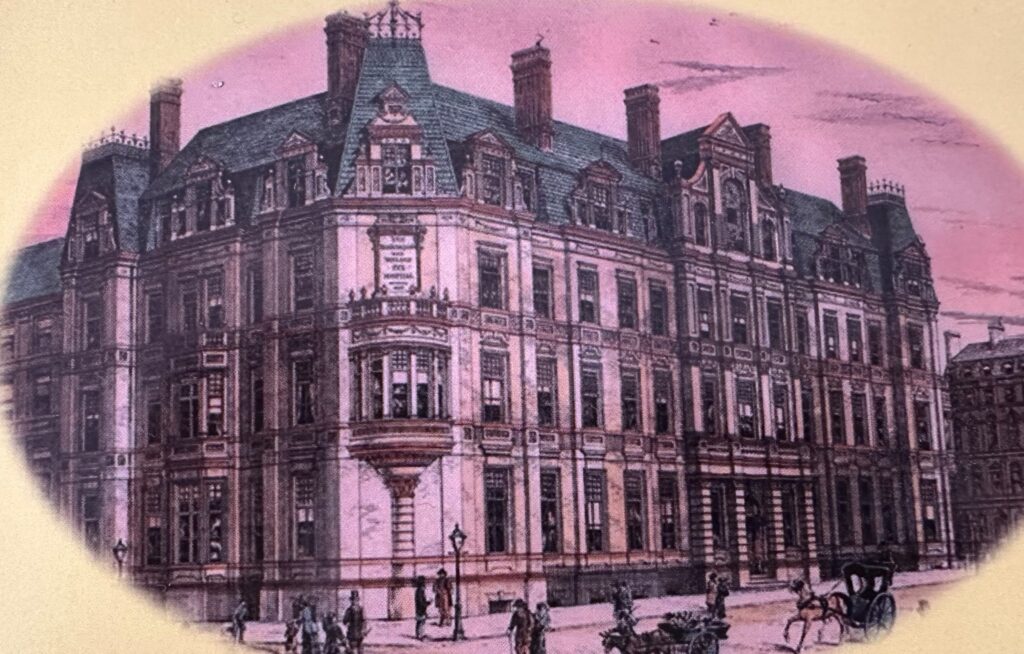

The ornate, early Victorian red brick building at Church Street in the old city centre, remained disused until 2000, when it underwent a luxurious makeover to become home to the 4 star Hotel du Vin & Bistro, but it still bares the iconic stone work that marked the Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital.

BMEC is currently one of the largest eye centres in Europe and is constantly developing to meet the demands of our ever changing society. Our main focus is the treatment and care of NHS patients with a wide range of eye problems from common complaints like cataracts to rare conditions which need treatments not available elsewhere in the United Kingdom. The centre offers a comprehensive and seamless ophthalmic service that is internationally renowned. The centre receives tertiary referral cases from throughout the Midlands and further a field. BMEC works on a Hub and Spoke Principle, BMEC being the hub, the spokes being Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Russells Hall Hospital and Solihull Hospital.

1800s

Joseph Hodgson, a British eye surgeon, started his campaign to open an eye hospital in Birmingham in October 1823. Six months later, in April 1824, The Infirmary for the Cure of Diseases of the Eye was opened at Cannon Street, Birmingham.

In 1853 after 30 years at Cannon Street, the increase in work at the infirmary meant a larger hospital was needed. To accommodate for this need, a house was bought in Steelhouse Lane and converted into a 15-bed hospital known as the Birmingham and Midland Eye Institution.

By 1861 the Steelhouse Lane property also became too small to accommodate the increasing number of patients the hospital was treating. The Steelhouse Lane property was offered to the Birmingham and Midland Free Hospital for Sick Children and the Birmingham and Midland Eye Institution moved out to a property in Temple Row in 1862, which provided room for 50-beds.

On the move to Temple Row the Institution changed its name again to the Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital.

The new Temple Row property carried a public house licence; the hospital governors renovated the public house, letting it out to a tenant. The hospital continued to own this inn for the next 20 years.

The new Temple Row property carried a public house licence; the hospital governors renovated the public house, letting it out to a tenant. The hospital continued to own this inn for the next 20 years.

Meetings were held in February 1880 as the hospital continued to grow to discuss remodeling the hospital on Temple Row to accommodate more patients. Architects involved in the plans for the remodel thought that in order to build a hospital large enough to accommodate its growth in patient numbers the building would have to be too tall to comply to the existing rights of light in place at the time.

By December 1881 these concerns had been resolved and the design for the building was agreed. The new building would include a waiting room to accommodate 200 people, two main wards, two contagious wards, an operating theatre, nurse’s rooms and a library.

The finished four-storey building designed in a Franco-Italian style by Payne & Talbot was officially opened on the 26th July 1884 by Lady Leigh, whose husband Lord Leigh had been president of the hospital.

In June 1892 an application to purchase a property in Edmund Street that adjoined the hospital was made. This property became a new wing opened in November 1895 by Viscountess Newport. This allowed the hospital to provide a children’s ward, an additional male ward and a pathology laboratory.

1900s

In 1909, a private ward block was opened.

A further adjoining property in Barwick Street was purchased and by 1910 was in use as a nurses and domestics home.

During World War 1 (1914-1918), the hospital provided 40 beds to the military authorities for the care of military personnel.

In 1914 the hospital begun treating Belgian refugees suffering from disease or injury to the eye and used a house in Sparkbrook donated to the hospital to home the refugees.

After the war the hospital received a letter from the 1st Southern General Hospital, thanking the governors for their services rendered during the war.

When the new hospital was opened in 1884 a room had been set aside for pathological investigations but it wasn’t until 1913 that the hospital had the services of a pathologist; before 1913 tests had been performed by the dispenser and reports issued by the consultant surgeon.

In 1918 Dr. H. Black took charge of the X-Ray department and Mr W. Meggeson, the dispenser, acted as a radiographer.

By the early 1920s a hospital training scheme was run with prizes of one guinea and ten shillings and sixpence being awarded to the two best nurses in each intake.

In 1932 both The Midland Orthoptic School and the Orthoptic department were founded.

Burcot Grange was gifted to the hospital in 1936 for use as a recovery home; this brought the total number of beds to 146.

During the period between the World Wars the hospital increased the services it offered; however advances in medicine also saw the ophthalmia neonatorum (conjunctivitis of a newborn) ward and clinic, the ultraviolet ray clinic and the septic theatre became outdated and closed.

1940s

In 1939 a site had been agreed for a new hospital near the Queen Elizabeth Hospital however World War 2 prevented progress. Following the war in 1946, plans were made once again for the site and were again abandoned.

There were several attempts to close the Birmingham & Midland Eye Hospital completely and open small departments in all the district hospitals. This would seriously have affected the work that the hospital had been doing in advancing ophthalmology.

In 1944 the Biochemistry department was established by Dr Dorothy Campbell.

In 1948 the Opticians department was opened. At this same time the Migraine clinic began to evolve from the Research department; by 1949 Dr K.M. Hay had established the department as a separate clinic.

1950s

Ophthalmic Nursing became a recognised speciality in 1952 and the Ophthalmic Nursing Board for Great Britain and Northern Ireland were set up. The hospital was inspected and approved by this new board as a recognized Ophthalmic Nurse training school.

1960s

In 1962 the Glaucoma department was established and the Retina department evolved from the Research department.

During the 1960s the Pathology department gradually developed until in 1963 a Regional Consultant Pathologist was appointed.

1970s

In 1971 Orbital surgery was first performed at the Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital.

1980s

In 1983 the Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital celebrated 100 years since its founding; thanking the likes of Priestley-Smith for his work in Glaucoma and Harrison-Butler for his use of the slit-lamp for the advancements in ophthalmology that aided in the advancement and diverse technical skills the hospital had to date.

At part of the celebrations a commemorative brochure was produced allowing us an in-depth insight into the hospital and the services it offered at this time:

- Optician’s department – offering refraction, contact lens and low visual aids services.

- Regional Migraine clinic – offering treatment involving not only the use of drugs, and diet but also psychological techniques.

- Glaucoma department – working on detection and investigation of glaucoma.

- Retina department – carrying out clinical electrophysiological diagnostic tests on pre and post-operative cases.

- Biochemistry department – running routine biochemical investigations and some specialised tests which they provided for hospitals in different parts of the country.

- Orthoptic department – dealing with diagnosis and treatment of patients with defective binocular vision or abnormal eye movements.

- X-Ray department – offering, pre-operative screening, investigation of systemic conditions and casualty work.

- Pathology department – comprising of haematology, microbiology and histology laboratories.

- Pharmacy department – dealing with around 60,000 prescriptions per year.

- Medical Ophthalmology clinic – investigating and treating patients with disorders such as retinal vessel problems and eye tumours.

- Fluorescein angiography department – diagnosing retinal disorders, including those resulting from Diabetes.

- Laser therapy – used for the treatment of retinal conditions.

- Orbital surgery – offering ultrasonography for the detection of orbital lesions and ocular ultrasonography for the detection of intraocular conditions.

- Photography department – providing a clinical recording and teaching service to the hospital in pre-operative and post-operative case as well as in diagnostic fluorescein angiography

- Medical social worker department – for patients with any kind of visual difficulties providing a liaison with other social workers and local authorities.

In 1983 the hospital also had a range of support services including: The Medical, Nursing and Paramedical sectors receive valuable back-up services from Administration/Clerical, Catering, Domestic, Portering and Works Staff.

Special clinics ran by the hospital in 1983 included: Cornea and specialised Ocular Trauma, Glaucoma, Medical Ophthalmology, Migraine, Neuro-ophthalmology, Ocular Motility, Oculoplastics, Ophthalmic Genetics, Retinal detachment/Vitrectomy and Ultrasonography/Orbital clinic.

In order to continue to provide excellent services the hospital took training and development seriously; in 1983 the hospital was the only undergraduate training centre for Ophthalmology in Birmingham. Nursing courses were also available for the Ophthalmic Nursing Diploma for Pre-registration and Post Registration Nurses, and the Ophthalmic Proficiency Certificate for Enrolled Nurses.

1990s

After 112 years at Church Street (1884-1996), the hospital moved to its current location at City Hospital on Dudley Road and was once more renamed as the Birmingham and Midland Eye Centre. The centre was officially opened on Friday, 28 June 1996 by HRH Prince Andrew.

2000s

The old hospital building at Church Street remained disused until 2000, when it underwent a makeover and became a 4-star establishment, the Hotel du Vin & Bistro, Birmingham.

The most iconic of all Birmingham hotels, this ornate, early Victorian red brick building in the old city centre, now part of the newly revitalised Jewellery Quarter, was sympathetically converted to provide 66 bedrooms and suites around a courtyard. Hotel du Vin & Bistro, Birmingham has incorporated all the original features including a magnificent sweeping staircase and granite pillars. The hotel still bares the iconic stone plaque on the side of its building.

The Story of BMEC - in the words of Michael Roper-Hall

The namesake of the prestigious Roper-Hall prize, Mr Michael Roper-Hall, shares his story of the development of academic and research departments at the now Birmingham and Midland Eye Centre.

The Story of BMEC

1934: Dorothy Campbell was a consultant in Coventry and accepted an invitation to establish our Research Department in 1934. As director (1934-1940) she researched Miner’s nystagmus and organised several courses in industrial ophthalmology. The Research Department existed under the direction of Dorothy Campbell several years before the appointment of a professor.

Many of us did some work in the department, but two in particular were Michael Hay and James Crews. Dr Michael Hay studied Migraine and ran a Migraine clinic and James Crews did a great deal of research into ‘Retinitis Pigmentosa’.

1945: At Birmingham & Midland Eye Hospital, I was House Surgeon in 1945 and Resident Surgical Officer in 1946. Around this time I was permitted to spend six weeks in Zurich to see the research and clinical progress that had been made in Switzerland during the years when the rest of Europe was at war and such progress was impossible. I was asked by Prof Amsler to write a report on ‘Research in Zurich’ and this was my first publication (BJO 1947; 31; 223-228).

1958: Between 1958 and 1975 I was appointed as a clinical lecturer of the University of Birmingham at Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital. I was then followed by Philip Jameson-Evans as Senior Clinical Lecturer and Tutor until the present Chair was establishes in 1988.

1960: In the 1960s a number of research associations and societies were formed. The Association for Eye Research (AER), one of the first in the UK was founded by Terry Perkins and soon went Europe wide. Several consultants from the Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital joined this research association and I was elected Chairman from 1969-1972. Towards the end of my time as Chairman the association merged with another research society and became the European Society for Vision and Eye Research (EVER).

1964: I recall in August 1964 Pseudomonas infections occurred on the main operating lists on the Thursday, Friday and Monday. My list was on the Tuesday and should have been cancelled but there was a lack of communication between the two firms and no information had been passed on.

1968: The Eye Foundation was set up in 1968 as a charitable body in order to obtain much needed equipment. Although this was its main objective there was always the aim of promoting research in conjunction with the University of Birmingham. The University was willing to establish a chair in ophthalmology if £55,000 was provided annually. The Foundation was soon successful in raising that sum.

1969: On the 17th July 1969 I attended the official opening of the academic unit. Alistair Fielder, who had been appointed as Professor, welcomed the guests before I gave a presentation giving insight into the background of the development. Following my presentation Gerard Coghlan gave the West Birmingham Health Authority view of future development and the value of the links between the NHS and the university. Before the formal opening Alistair thanked the Birmingham Eye Foundation, Hale-Rudd Trust, West Birmingham Health Authority and the University for their Support. The formal opening and the unveiling of the plaque then took place, performed by Sir Adrian Cadbury.

1971: By 1971 the foundation had enough funds and the university was ready to establish a chair for a Professor to hold half of his appointment in clinical work, unfortunately the NHS were unable to fund new sessions which halted progression for several years.

1972: With James Crews and the Architect John Humby, I visited newly built Eye Hospitals in Europe and wrote an article ‘Planning of a 100 bed Eye Hospital’ published in 1972.

1973: I served on the Council of the Royal College of Surgeons from 1973-78 and on its Academic Board from 1973-75.

1979-1985: James Crews, who I had previously visited Europe with, held complementary sessions with me during this time. He specialised in Retina and established the retinal clinic. He researched retinitis pigmentosa and other familial retinal conditions. He was appointed as Professor at Aston University.

1985: In February 1985 I resigned from the NHS. There were several reasons for my resignation at that time but one was that it would help the progression of the academic unit by giving enough sessions to cover the clinical work of a Professor or Senior Lecturer. It took four years to finalise the job description, send out the advertisements and make the first academic appointments. I worked doing my own locum during this time until 1990 when the Chair was established.

1988: In 1988 Alistair Fielder was the first to be appointed to the new chair of ophthalmology in the University of Birmingham. He remained chair until 1995. Phillip Murray took over from Alistair gaining promotion to Professor after five years as a senior lecturer.

My highlights of research at Birmingham & Midland Eye Hospital:

Joseph Hodgson (1823-1835) was a general Surgeon at General Hospital Birmingham, but had a strong interest in Ophthalmic Surgery. Thus he founded and then worked as a consultant at The Infirmary for the Cure of Diseases of the Eye.

He appointed Bowman as a young man to prepare specimens, examine them with a compound microscope and make drawings. It is relevant that he studied specimens from eye and kidney while at the Birmingham & Midland Eye Hospital.

William Bowman was the first, or among the very first, to apply the compound microscope to biological problems. When he had completed the work given, Hodgson presented him with this microscope. He took off to London to qualify in medicine. He then used the microscope to publish much on histology between 1838 and 1849.

D Priestley Smith (1913-1916), contributed to the development of the perimeter and published his work on investigations on Glaucoma in 1978. He was awarded the Jacksonian Prize (in Medicine) for his essay on Glaucoma in 1879. He delivered the Bowman lecture in 1898 on Convergent Strabismus. He later became Professor of Ophthalmology and held a personal chair in Ophthalmology at University of Birmingham.

T Harrison Butler (1913-1930) introduced the slit-lamp to this country, he had many talents; wrote extensively; was a great teacher and designed many ophthalmic instruments often described as ‘Birmingham Pattern’.

Dorothy Campbell (1934-1940), a consultant ophthalmologist at the Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital, opened the Research Department at BMEH and studied Miner’s nystagmus and other occupational eye conditions. She organised a series of courses on Industrial Ophthalmology.

James Crews (1959-85) specialised in Retina and established the retinal clinic. He researched retinitis pigmentosa and other familial retinal conditions. He was appointed as Professor at Aston University.

Research milestone highlights:

Birmingham and Midland Eye Hospital was one of the first eye hospitals in the country to:

- Import and use the integrated Haag-Streit slit-lamp microscope

- Introduce microsurgery. In 1957, microsurgery started with the use of the coaxial Zeiss microscope (OpMi 1) with which the field of view was directly illuminated

- Introduce cryosurgery

- Introduce trabeculectomy operation for glaucoma

- Pioneered enzymatic surgery, advances in cataract surgery and the use of intraocular lenses

- Introduce photocoagulation for the treatment of diabetic retinopathy and other retinal conditions (first with the Xenon Arc, then with Ruby, Argon and Indo-cyanine green)

- Start an Ultrasound clinic

- Pioneered the use of static and automated perimetry